On Mermaids & Men Making Shit Up

An incomplete history of men revising the stories of powerful women that make them uncomfortable --- from mermaids, to me, to you

The mermaid is grotesque—less skeleton and more dried jerky stretched over bones. Skewered on a metal pole, she is about four feet long from tip to tail. Her mouth hangs open in a wide snarl that shows two rows of pointed teeth. Her cheekbones jut with such angular ferocity that they look capable of puncturing a balloon. Dried, white hair dangles from her head. A strange puzzle of bones is held together by brittle, taxidermied skin. There is a rib cage, needle-thin arms, webbed hands, and, of course, the tail. It bulges and twists at unlikely angles, hewing closer to a child’s clumsy paper-mache project than a fishtail. Above the exhibit is a sign that reads, “No Pictures.” It makes sense. I doubt anyone would pay if they knew this was the promised mermaid.

This is the Fort Fisher Mermaid, one of the many oddities I saw when I visited Wilmington’s Museum of the Bizarre. Local lore says Captain Tucker discovered the skeleton of this mermaid on the beaches by Fort Fisher. With a sailor’s superstition, he kept his discovery a secret, storing the mermaid in his boathouse and only showing her to his closest friends. When he died, his grandson donated the skeleton to the Museum. As I looked at the thing, I understood why.

Clearly, this “mermaid” was man-made, and as I left the exhibit and walked along the Cape Fear River boardwalk, I wondered what could have motivated Captain Tucker to create such a hideous manifestation of the mythical mermaid. Men have been imagining mermaids for millennia. In fact, at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, where the Haw and Deep rivers converge, there is a rocky outcropping known as Mermaid Point where revolutionary war soldiers repeatedly claimed to see mermaids brushing their hair in the moonlight. But there’s a bright line between claiming to see a mermaid in the moonlight and manufacturing a skeleton.

Captain Tucker was not the first to fake a mermaid, though. Museums around the country—and the world—have similar mermaid skeletons in their collections. Perhaps the most famous man-made mermaid is the “Feejee” mermaid, a specimen purportedly purchased from a fisherman in the Fiji Islands. In the 1840’s, P.T. Barnum of the famed Barnum & Bailey Circus exhibited the mermaid in New York, Boston, and London. He printed close to ten thousand pamphlets promoting the first exhibition in New York. These pamphlets depicted three, beautiful mermaids, with long flowing hair, pert breasts, and curling tails. But when curious visitors came to see Barnum’s mermaid, they were shocked. Later examination has found that this so-called mermaid was likely the top half of a juvenile monkey sewn to the bottom half of a fish, with various other appendages added, such as shriveled, pendulous breasts. Some visitors had to leave the exhibit, others became ill, but, despite this, most believed that they had indeed seen the shriveled remains of a true mermaid.

With these bestial collages, men made monsters of mermaids. In attempting to make manifest the creatures they had mythologized, they created something much uglier and smaller. But men have not just manipulated monkey bones and fish scales to make mermaids; as early as the Middle Ages men have meddled with the heart of the mermaid myth. Their handprint burns bright red on the beautiful, bare chest of the diminished, contemporary mermaids we are familiar with today.

I grew up reading Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid and watching Ariel in Disney’s animated movie rendition of the same tale. My fingers fluttered over the shimmering scales in my storybook, scales that caught the light when you flipped the page, glinting like a fish flashing just beneath the water. I watched as Ariel’s voice floated along a trail of sparkling smoke towards Ursula, the evil sea witch. I recoiled in fear from Ursula, briefly afraid of toilets with automatic flushes because I thought their watery depths seemed a likely place for her to reside.

In fact, mermaids of early myth were much more like Ursula from Disney’s motion picture than the sugary sweet Ariel. Mermaids of early myth were inaccessible to men. Their tails forbade penetration. Their underwater world would drown any male suitor who might pursue them. They were strong, able to out-swim any man. They had the power to sink or save an entire ship. They did not need men. And, in fact, men needed them.

It is largely agreed that the first iteration of a mermaid in historical records is the Assyrian goddess, Atargatis. Often depicted with the long tail of a fish and the torso of a woman, the Assyrians worshiped Atargis, building huge temples to honor her. Water has often been associated with femininity and fertility, so many of the earliest mermaids were believed to have power over the fertility of not just a community’s people, but its land as well. In Africa, a pantheon of water deities referred to as Mami Wata, were depicted as half-women with either fish or snake tails. These Gods were thought to govern all natural cycles, including the flow of rivers like the Nile. As the Greeks and Romans appropriated these myths and made them their own, however, a shift in the stories surrounding mermaids occurred. There were nymphs, sirens, water sprites, and naiades—a variety of feminine water creatures—but none depicted with the characteristic mermaid tail. The one notable exception to this is Thessalonike, a mermaid from Greek mythology who is tempestuous and vengeful, known to sink entire ships of sailors in grief for her lost love. Thus, mermaids became less deities and more fickle creatures—powerful still, but not all-powerful. Sailors feared the bad luck they brought, but also began to affix topless statues of them to their ships’ prows, believing that the audacity of a topless woman would cow even the ocean into submission.

While men like Captain Tucker and P.T. Barnum created physical manifestations of these unattainable creatures to possess, to hang from the rafters of their boat house, other men contented themselves with further re-writing the mermaid, crafting a hyper-sexual being utterly stripped of her previous power—a creature dependent on men for survival.

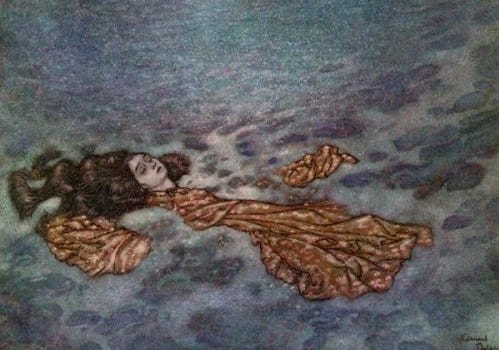

Perhaps no story does this more deftly than Hans Christian Andersen’s, “The Little Mermaid,” originally published in Denmark in 1837. In this story, the only reference to the mermaid myths of old is Marina’s (the little mermaid’s name in this version) body. She resembles the carvings found in old Assyrian temples—half-woman, half-fish—but the similarities end there. Marina is a mermaid disempowered. She does not wreck ships as Thesolinike did, but saves men from shipwrecks. She does not control the flow of the Nile. In fact, she cannot even speak, having traded her voice for a pair of legs so she can walk on earth with the prince she has fallen in love with. She does not concern herself with the fertility of entire communities of women. Rather, her only concern is her prince and whether she will succeed in making him love her. Finally, in a symbolic literary act, Andersen concludes the story by making Marina disappear entirely. He rips the mermaid from her body, so that just a few years later, Barnum can shove her into a swindler’s skeleton. In an ending that differs sharply from the Disney version many are familiar with, Marina fails to capture the heart of the prince, and becomes sea foam, before rising above the waves to become air, all that she once was, vanishing.

Disney adapted Andersen’s version for the silver screen, and the flick of his pen cemented the transformation of mermaids in our popular consciousness. While Marina is described as beautiful in Andersen’s tale, her counterpart, Ariel, in Disney’s classic film, is downright sexy. Her waist is impossibly small, her torso completely exposed but for two suggestive clamshells that cling to perky breasts. Her hair is long and flowing, her eyes big, blue, and always batting. When she transforms into a human, in contrast to Andersen’s tale, she swims nude through the ocean to reach her prince, somehow losing her clamshell bra despite the fact that only her bottom half transformed. For a long scene after, she covers herself in fishnets and sails, both falling away from her body with every motion. She is beautiful, voiceless, helpless. I think if Atargis swam past Ariel in the sea, she would not recognize her as kin.

I watched Disney’s version of The Little Mermaid frequently in my first year of college. My best friend and I would swig hydrocodone, left over from my latest bout of chronic bronchitis, and watch Disney movies. The golden liquid would cast a golden hue upon those childhood films, and, cozied up together in my twin bed, to-go container of fries between us, they seemed almost magical. Our favorite was The Little Mermaid. We would giggle along to Sebastian’s rendition of Under the Sea, rolling with laughter the way only high teenage girls can. Everything was warm, and soft, and glowy, huddled there together beneath the dim strip lighting. But beyond the four walls of my dorm single was a world Disney had not prepared us for.

Scholars have hypothesized that men’s fascination and fear of the mermaid stemmed from the mermaid’s sexual inaccessibility. Mermaids may be beautiful, but men could never truly have full sexual power over them. Couple that with mermaid’s physical and magical powers, and they have the potential to emasculate even the strongest of men. So men found their power through their belittling reclamation of the mermaid myth, and, in extreme cases, through the creation of horrific bodies that they could possess fully.

In our first semester of college, Stella and I were each sexually inaccessible in our way, each later made monstrous by the boys who simply couldn’t allow us to have that power. Stella grew up in a conservative, southern town, where she attended an all-girls, private, Christian school, and was always under the watchful eyes of her grandparents. In college, she wanted to have fun. Stella was unabashedly sex positive, thrilled to be in a place where she could finally be free. In our first year of college, she had sex with a lot of boys. Every weekend she would regale me with fascinating, funny, awkward stories, updating her spreadsheet of boys as we ate Bojangles hungover. Boys had no power over Stella, because she almost never slept with the same one twice. She was supremely unbothered, here for a good time, not a relationship.

I was the opposite. I had also grown up in a conservative, southern town too, but I was raised by two Catholic parents and was still a virgin who planned to stay that way until I met someone I loved—a boyfriend. Boys had no power over me, because, despite their fetishization of ‘taking my virginity,’ I wouldn’t sleep with them. My legs might as well have been a mermaid’s tail. We were eighteen years old. Our tits were perky. Our shirts were cropped. We grinded against each other in the hedonistic basements of fraternities, glitter raining from our hair like gold. We were the fertility goddesses of original mermaid myth. We were so naive to think it could last. Like Andersen and Disney, the boys retold our stories, and in their version we were far from powerful.

In their stories, Stella was a whore. I heard other boys who had slept with call her a slut, scorning her behind her back. Then, they made up a new story about me, a story based in pernicious stereotypes about the type of girl who doesn’t have sex freely. Of course, they called me a prude. But the things they said after I lost my virginity were worse. The boy dumped me soon after—on my nineteenth birthday—and then made up a vicious rumor to justify his actions. Being a “good-girl,” a Catholic virgin, had given me a sense of control. But he turned that identity against me, telling his entire fraternity that I had not been on birth control, that I had gotten pregnant, that I had refused to get an abortion, and begged him to stay with me to raise the child. This is so blatantly false that I thought it was a joke when I first heard it. I was on birth control. I have never been pregnant. I was a double-major, double-minor with a 4.0 GPA. Why would I give that up to start a family at nineteen? But just as Andersen and Disney’s stories stuck, so did theirs. We became, in popular consciousness, the skank and the psycho. The stories of who we were before disappeared, like seafoam evaporating into sky, leaving only a trace of sour air behind.

Then, since we were already monsters in myth, we made monsters of our bodies too. We both developed eating disorders, as if we could starve ourselves back into the fold. My ribs jutted beneath my skin in a way eerily reminiscent of the Fort Fisher Mermaid. We didn’t stop going to parties, but there was an anxious sort of desperation in our dancing now, jaws clenched from key bumps, teeth grinding madly. I was reminded of Andersen’s mermaid; each step she danced was agony, but the prince wanted her to dance, so dance she did. We got into Xanax, swallowing bars with swigs of Keystone Light. Xanax made everything fade into a pillowy black. We were thin and blank, like slate. And the boys wrote whatever they wanted upon us. As they have always done.

But beneath these false narratives and hoaxes, there is always the hard core of truth. Beneath the taxidermied skin are verifiable monkey and fish bones that discredit the lie. I still got questions about that rumor into my fourth year of college. But I continued to tell my story, and like P.T. Barnum and Captain Tucker, the cracks began to show in the falsehoods. Beneath the glossy, sexualized, disempowered mermaids, far below in the fierce currents of the world’s ocean, flows the indomitable, undeniable story of those first mythological mermaids.

I think there was always something in me that perceived this strength of mermaids underneath all the frills and falsehoods. In summer, in the neighborhood pool, I would spend hours playing mermaid, sometimes with my sisters, sometimes alone. With my legs flush against one another, down to the tips of my flexed feet, I would kick my makeshift tail, loving the rush of water along the length of my bare legs, the thrill of propulsion, the strain of hardening muscles in my thighs, my core, as my body moved as one, like a whip through water, crooked then straight.

I love this so much. I also am fascinated by the mermaid myth, how worldwide it is; I’ve been writing a series based on mermaids and lies made up about them. I’m currently editing book 3.

It’s true - they will lie to make us look like Ursulas.

They don’t realize that Ursula isn’t a bad person to be. I think that, in my adult life, I’ve sort of admired her more!

Great post!

"their tails forbade penetration". why haven't i thought of it like that before!